Posing 30 Questions

1. Why is there a picture of a woman’s reproductive system at the top left?

2. What do the pink stars with K7 in them represent?

3. What type of paint was used?

4. Why do two of the men have such outlandish hairdos?

5. Why is one man wearing a suit but all the others are dressed casually?

6. Is the barbershop based off of one the artist has visited?

7. Why are the figures painted such a dark black?

8. Why is the clock at 3:37PM?

9. When was this painted?

10. Is this painting similar in style and content to other paintings this artist has done?

11. What is the name of this painting?

12. Why are all the figures facing the viewer?

13. What is in the white drawers?

14. Why is there no perspective?

15. What kind of plant is that on the left?

16. What does this painting communicate to black people?

17. Why did the artist choose to cut off the man on the far left?

18. What historical context is the style drawing from?

19. Which area of the artwork is emphasized by the artist? Why?

20. How would you describe this artwork to someone who has never seen it?

21. Why do you think the artist created this work?

22. What emotions do you feel when looking at this?

23. What does this artwork remind you of? Why?

24. If you could change this artwork, how would you change it?

25. What is strange about this painting?

26. What is boring about this artwork?

27. What is missing from this artwork?

28. How do you think the artist feels about the final product?

29. What do you think happened before this scene?

30. What do you think happened next?

Information About the Work

“De Style is a modern-day genre scene that expresses a sense of community and male bonding that is quite unlike the sanitized images of African-American life presented in television situation comedies. It is 3:35 in the afternoon; a group of young men and a barber hang out in the barbershop, staring at us as if we had just interrupted their conversation. This naturalism is belied by their elaborate hairdos: one is topped with what seems to be a royal tiara, another resembles a traditional Yoruba beaded crown. Each bears attributes – outsized gold jewelry or spiffy clothes – that mark his individuality. “Black people occupy a space, even mundane spaces, in the most fascinating ways,” Marshall observes. “Style is such an integral part of what black people do that just walking is not a simple thing. You’ve got to walk with style. You’ve got to talk with a certain rhythm; you’ve got to do things with some flair. And so in the paintings I try to enact that same tendency toward the theatrical that seems to be so integral a part of the black cultural body.” The title of this painting, De Style, is itself a clever pun on black vernacular accents as well as on the abstract modernist art movement de Stijl, an inside joke Marshall incorporates to underscore the complexities of language and the unintended interpretations that are often attached to the way we communicate.” (Marshall, et al, 2000, p. 16)

“The problem was how to bring that figure close to being a stereotypical representation without collapsing completely into stereotype. I was playing at the boundary between a completely flattened-out stereo· type, a cartoon, and a fully resonant, complicated, authentic representation – a black archetype, which is a very different thing. The archetype allows for degrees of complexity that the stereotype always minimizes or undermines. That was the idea behind the very black figures in The Lost Boys and De Style (pages 65, 67) and other paintings I did at that time.” (Marshall, et al, 2000, p. 117)

“I started De Style just as I was finishing The Lost Boys. It was called De Style because, just as I had taken an Italian model for The Lost Boys, based on the Renaissance pyramid and the grid, I adopted a Dutch style, De Stijl, for this next painting. I loved the work of Piet Mondrian, so I combined his rectilinear composition with some elements from vernacular folk painting. The title is in dialect: you say de instead of the. The painting is about more than hair styles, though it’s set in a barbershop; a barbershop is a place where people go to be styled and become stylish. At this point I was loadir!g the paintirlgs with as many different kinds of things as I could, in a way that sometimes seems arbitrary, but isn’t. One of my goals in life had been to get a work of mine into the museum among the work of artists that I went to the museum to admire. I realized that dream when the L.A. County Museum of Art, the first museum I had ever entered, bought De Style.” (Marshall, et al, 2000, p. 118)

“In 1993, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art purchased De Style, the first work by Kerry James Marshall to enter a maJor American art museum collection. The work depicts the interior of a neighborhood barbershop – a place of creative work, community, and self-transformation-where the hairdresser and his smartly dressed male clientele are staged as 1f they were the aristocratic subjects of Hans Holbein’s sixteenth-century double portrait The Ambassadors,1 The work space that Marshall describes in De Style was inspired by experiences close to his childhood home on Forty-Sixth Street in South Central Los Angeles. The house, to which his family moved in 1964 from Nickerson Gardens Projects in Watts, was owned by Mr. Walker, a local barber. Walker taught Marshall and his older brother, Wayne, how to shine shoes, and the boys would earn bits of cash in the shop by attending to patrons’ soiled footwear or sweeping up hair clippings. Much like the array of scholarly accoutrements that symbolize the worldliness and intellectual prowess of Holbein’s two noblemen, the barbershop in De Style is full of vibrant curiosities and tools of the trade. These trappings speak to the elegant power of Marshall’s fashionable subjects and the cultural memory that such a site embodies; the painting is blissfully radical in the way it catalogues and celebrates a different kind of male power. The artist’s subjects are not merely urban but distinctly urbane, and it is this urbanity that underpins not only De Style but also Marshall’s entire remarkable artistic project.” (Alteveer, et al, p. 17)

“The boastful painting is rich with details, contrasts, and allusions; the name Zenith on the radio also winkingly suggests Marshall’s sense of pride in this painting (which was acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art the year it was created). The title is a play on De Stijl, the Dutch artistic movement founded in 1917 that advocated a rigorous form of abstraction and whose best-known proponent was Piet Mondrian. The title is also a vernacular pronunciation of “the style.” In De Style, Marshall sneaks into the picture the rectilinear compositional structure and flat planes of color that are characteristic of Mondrian: the red rectangles of the sides of the counter, the white of the counter’s drawers, the wavy quadrangle of blue that hangs in the upper left corner, and the yellow of the trashcan create a syncopated visual rhythm that gleefully recalls Mondrian’s own. The pink of the sink and of the starry bursts that read “K7” (the name of a hair conditioner) that float across the canvas evoke a particular shade used by Mondrian in a handful of his early paintings14 as well as the color of K7’s plastic jar.

By hiding abstraction within a figurative painting, Marshall inverts the process whereby Mondrian arrived at pure abstraction after first gradually paring down figurative elements in his work. It also allows the figures in De Style to resonate as abstractions in and of themselves. As in Past Times, the figures’ faces are nearly identical, whereas differences in hairstyles reach a baroque height. The towering hair of the figure on the left is formally matched by the spindly plant behind him, a move that further points to linkages between abstraction (the hair is an abstract construction) and nature. The commanding, flat figure on the right, whose black suit is the same color as his skin and hair, functions like an anthropomorphic plane of blackness. Mondrian wrote in 1937 of the instability of the terms figurative and nonfigurative, remarking that “every form, even every line, represents a figure, no form is absolutely neutral.” De Style is electrified by Marshall’s keeping in play this non-neutrality and his incongruous translation of Mondrian’s formal principles into a seemingly vernacular scene.

There is also an unsettling absence in De Style, one that becomes noticeable only after taking in the pleasures of the painting’s chromatic theatrics. On the far left, a seated figure wears a gigantic ring that reads “STUD.” His head and half of his torso are cut off by the edge of the canvas; it is a partial fragment of a figure. However, the figure’s shirt, like a modern veil of Veronica, bears a partial image of a face painted in blood red. 15 (Red, like black, has a complex material and metaphorical valence.) Although in Oe Style, painting is clearly alive and well, the barbershop is a melancholic scene, and black is the color of mourning.” (Alteveer,, et al, p. 64)

“By Marshall’s own admission, De Style marked a major breakthrough for him, in part because of its impressive size; at nearly ten feet tall by ten feet wide, it was a radical departure from the small paintings and collages he made in the 1980s.1 Marshall was newly developing his methodical investigation of the historical genres of Western painting, and his choice of where to begin was not accidental. Referring to De Style, Marshall said, “I think it’s important for a black artist to create black figure paintings in the grand tradition. Artworks you encounter in museums by black people are often modest in scale. They don’t immediately call attention to themselves. I started out using history painting as a model because I wanted to claim the right to operate at that level.” 2 Acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art soon after it was completed, De Style was also the first of Marshall’s works to enter the collection of a museum-in fact the very same museum where as a child he had his formative exposure to art in “the grand tradition.”

Marshall envisioned De Style in the lineage of history painting, but its subject, a barbershop featuring African American men and a woman, is just as notably a genre scene, an image of everyday life. Marshall grants this common setting the heightened attention and distinguished treatment once reserved for decisive historical events. He further signals the importance of his subjects through the arrangement and poses of the figures, which evoke the stately portraits by sixteenth-century painters such as Hans Holbein. (Marshall quotes elements of Holbein’s The Ambassadors more explicitly in School of Beauty, School of Culture [2012], a thematic sequel to De Style arriving nineteen years later.) The title De Style is tied to the name of the barbershop, Percy’s House of Style, which is reflected in the mirror behind the barber. Yet this vernacular phrase is also an oblique allusion to De Stijl, the Dutch art movement launched in 1917 that is often identified with Piet Mondrian. In the background of the painting Marshall weaves in visual references to Mondrian’s rigorous, rhythmic abstractions: parts of the counter, walls, and trashcan are painted red, blue, or yellow, embedding within the barbershop a dispersed pattern of rectangular shapes in Mondrian’s signature colors.” (Alteveer, et al, p. 116)

Influential Works of Art

In the words of Kerry James Marshall himself, these are famous works that have influenced his art and De Style in particular.

Examples of Other Work by the Artist

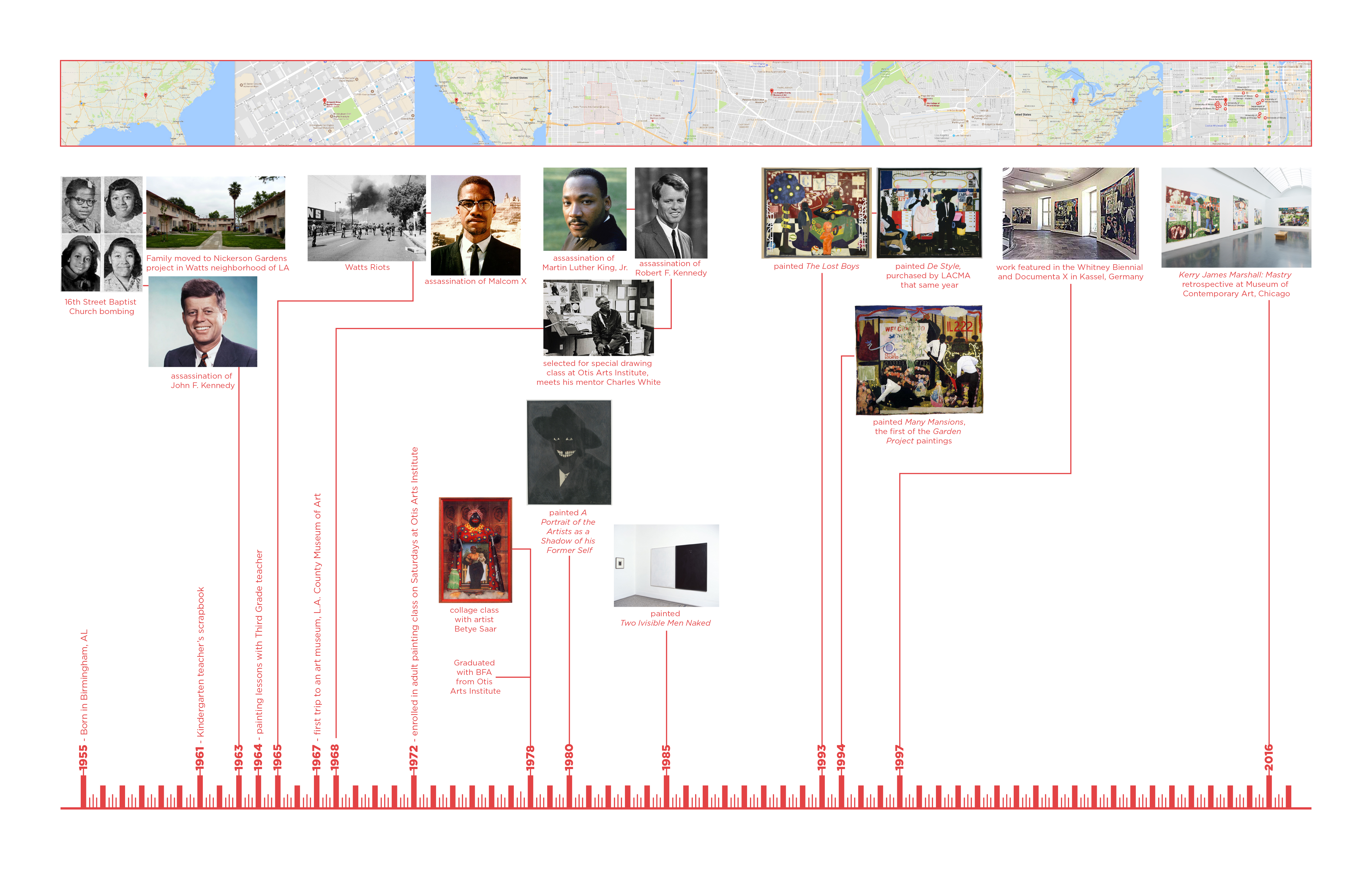

Timeline of Important Events in the Life of the Artist

Historical Context

Kerry James Marshall is often quoted as saying, “You can’t be born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955 and grow up in South Central [Los Angeles] near the Black Panthers headquarters and not feel like you’ve got some kind of social responsibility. You can’t move to Watts in 1963 and not speak about it. That determined a lot of where my work was going to go…”. Birmingham, Alabama was the epicenter of racial violence and Civil Rights activism in America in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1963 the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed by the Ku Klux Klan. This vicious attack killed four young black girls, and injured 22 others. After that, Kerry Marshall’s family, like many other black families, left Birmingham for a part of the country they felt would afford them more opportunity and greater safety for their children. Two years after moving to the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, Kerry James Marshall watched the Watts Riots from a nearby friend’s attic window.

After initially moving to the Nickerson Gardens Project in Watts in 1963, Marshall’s family moved a year later to a house on 64th street in South Central Los Angeles. The house was owned by a Mr. Walker, who was a local barber. Kerry Marshall and his brother worked in Mr. Walker’s barber shop, shining shoes and sweeping up hair clippings (Alteveer, Molesworth, Roelstrate, Winograd, 2016, p. 17). Without a doubt, this experience would influence Marshall later in his career when he was working on De Style.

Marshall graduated from Otis Arts Institute in 1978. In 1980 he painted A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, his first painting of what would later become his signature image. At the time he was trying to create artwork that was political in nature, but was having difficulty responding to current events with paintings in a timely manner. To that end, he endeavored to simplify his methods and focus on abstract collages and more illustrative methods. For this painting, Marshall wanted to create a “very visual” representation of invisibility (Marshall, Sultan, & Jaffa, 2000, p. 117). The subject was painted all in black, on a black background, with only subtle hue changes separating the two. The eyes and teeth were rendered in bright white. It was a conceptual breakthrough for Marshall and it was at this time that he decided, “whenever I painted an image of a person, it would always be a black image, and that image wouldn’t be a personality so much as it would be an image that spoke directly to the issue of blackness” (Marshall, et al, 2000, p. 12).

Marshall painted De Style in 1993. In Marshall’s own words, history painting has had a strong influence on him, and he was fascinated by artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Jacques-Louis David, and Hans Holbein (Marshall, et al, 2000, p. 118). Of course, De Style is also influenced by the geometric paintings of Piet Mondrian. Marshall started De Style just as he was finishing another of his seminal paintings, The Lost Boys, which was based on an Italian Renaissance style. He adopted a Dutch style for his next painting and titled it De Style, which is of course a play on De Stijl, the art movement founded by Mondrian (Marshall, et al, 2000, p. 118). Marshall’s black archetype that he had been developing for over ten years, was fully realized in these two paintings, The Lost Boys and De Style.

By the end of the 1980s, the art world debate over whether painting was dead or alive had ended, as Irving Sandler writes in his book on Postmodernism. Painting was once again accepted as a “viable, artistic option” (Sandler, 1998, p. 544). Many who had previously criticized painting were now of the opinion that painting was “capable of certain kinds of expression that no other art form could deliver” and by the early 1990s a “new group of artists with a multicultural message had come to the fore” (Sandler, 1998, p. 544). Art theoreticians were embracing multiculturalism. Authenticity and genuine cultural representation were now seen as important (Sandler, 1998, p. 550). One of Marshall’s life goals at this point in his career was to get a work of his into a museum, alongside the artists he admired. This goal was achieved when, shortly after it was completed, De Style was purchased by the L.A. County Museum of Art. Coincidentally, LACMA was the first museum Kerry James Marshall had ever visited (Marshall, et al, 2000, p. 118).

Related Classroom Materials

Writing in Response to the Work of Art

Creating in Response to the Work of Art

Facilitating Dialogue with the Work of Art

I conducted a one-on-one Interactive Art Lesson with the son of a family friend, based on Dialogue 2. Below is a video of that lesson highlighting a few select moments of what I feel were my instructional strengths, and my least creative instructional moments.

Bibliography

Gude, O. (2000). Drawing Color Lines. Art Education, 53(1), 44-50.

Marshall, K. J., Sultan, T., & Jaffa, A. (2000). Kerry James Marshall. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams.

Alteveer, I., Molesworth, H. A., Roelstrate, D., Winograd, A. (2016). Kerry James Marshall: Mastry. New York, NY: Skira Rizzoli.

Sandler, I. (1998). Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the early 1990s. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.